by Regency Romance Author, Donna Hatch

Few symbols of Christmas are more admired than the Christmas tree, and nowadays, most countries that celebrate this holiday have their own version of Christmas trees. Before that, evergreens were a commonly hung adornment in homes, not just at Christmas but all winter.

Dating back hundreds of years, people in many countries hung evergreen boughs over their doors and windows, hoping to ward off witches, ghosts, evil spirits, and even illness. According to legend, it wasn’t until about 722 in Germany, that whole trees arrived on the scene. In the Middle Ages, the Germans and Scandinavians brought evergreen trees to the door or sometimes even inside their homes to display their hope that spring would soon come. It also symbolized eternal life.

One popular story about the origin of the evergreen being a Christmas tree tells of Saint Boniface who encountered a group of pagans about to sacrifice a child at the base of an oak tree. Appalled, and rightly so, Saint Boniface stopped the sacrifice and even cut down the tree to prevent future sacrifices. Later, a Fir tree grew at the base of that oak stump. St. Boniface took that as a sign and spread the word that the evergreen was a holy tree because its branches pointed to heaven as a sign that it belonged to the Christ child, and that the fir was a symbol of His promise of eternal life.

Another legend attributes Martin Luther the credit for the origin of the Christmas tree. In the 1500’s on Christmas tree, Mr. Luther took a walk through a snowy forest. The sight of the moonlight shimmering in on the snow-covered woods that starry night touched him so much that he cut down a small fir tree and brought it home for his family. They decorated the tree with small lit candles in honor of the birth of the Christ child.

According to All About Jesus Christ, The Origin of the Christmas Tree:

Research into customs of various cultures shows that greenery was often brought into homes at the time of the winter solstice. It symbolized life in the midst of death in many cultures. The Romans were known to deck their homes with evergreens during Kalends of January 15. Living trees were also brought into homes during the old Germany feast of Yule, which originally was a two month feast beginning in November. The Yule tree was planted in a tub and brought into the home. But there is no evidence that the Christmas tree is a direct descendent of the Yule tree. Evidence does point to the Paradise tree, however. This story goes back to the 11th century religious plays. One of the most popular was the Paradise Play. The play depicted the story of the creation of Adam and Eve, their sin, and their banishment from Paradise. The only prop on the stage was the Paradise tree, a fir tree adorned with apples. The play would end with the promise of the coming Savior and His Incarnation. The people had grown so accustomed to the Paradise tree, that they began putting their own Paradise tree up in their homes on December 24.

The Hanoverian kings, who were from a duchy of what became present-day Germany, adopted the use of Christmas trees -- the tabletop variety -- with real lit candles. While the candles were lit, a footman or a member of the family stood by with a water pot to prevent the risk of causing a fire.

Christmas trees came to England with the German Prince, Albert, when he married Queen Victoria in 1840, and brought his German Christmas traditions with him. In 1848, an engraving of the Royal Family celebrating Christmas at Windsor was published in the newspaper which showed Victoria and Albert standing with their children around a Christmas tree. Since the English adored Queen Victoria, the general populace adopted the custom of a Christmas tree with ornaments.

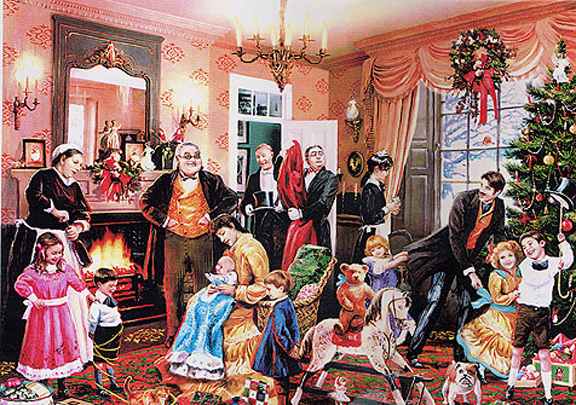

German immigrants brought the Christmas tree to America as early as 1747. Pennsylvania had the first record of one being on display in the 1830s. The average American in New England, however, rejected Christmas trees, viewing them as pagan symbols. Puritans viewed Christmas as sacred and shunned anything they considered frivolous. However, with an influx of German and Irish immigrants, the Puritans lost their power, further fueled by the illustrated version of the newspaper that had a sketch of the royals with their tree. After all, what was done at court immediately became fashionable—not only in England but with fashion-conscious East Coast American Society. This combination eventually undermined the Puritan legacy. Never to do anything small, the Americans soon graduated from small table-top trees such as the Europeans used, to the floor-to-ceiling trees we know today.

As a Regency author, I seldom use Christmas trees in my stories unless I establish a family tradition with German roots for my fictional characters. But there are lots of other English fun traditions I discovered, after much careful research, that were honored, and that I include in my writing. Many of those traditions, including Yule Logs, Mistletoe or kissing balls, and other fun Christmas traditions went into my full-length novel, Christmas Secrets, available in print and ebook, and free on Kindle Unlimited. You can purchase your own copy, or give it as a gift, here:

A stolen Christmas kiss leaves them bewildered and breathless.

A charming rogue-turned-vicar, Will wants to prove that he left his rakish days behind him, but an accidental kiss changes all his plans. His secret could bring them together...or divide them forever.

Holly has two Christmas wishes this year; finally earn her mother's approval by gaining the notice of a handsome earl, and learn the identity of the stranger who gave her a heart-shattering kiss...even if that stranger is the resident Christmas ghost.

Grab your copy on here!

Don't have time to read a full-length novel during the holiday season? Check out these novellas, short enough to enjoy and romantic afternoon escape, and long enough to have a swoony happily ever after.

Sources:

https://www.britannica.com/plant/Christmas-tree

https://www.regencyhistory.net/2012/12/did-they-have-christmas-trees-in-regency.html

https://www.allaboutjesuschrist.org/origin-of-the-christmas-tree-faq.htm