Another tradition was to serve a rum punch, apparently a favorite Christmastide ritual for Charles Dickens. The making of the punch was quite a production, and Dickens would explain each step to his guests as they watched the punch being concocted. The drink is made in a large fire-proof punch bowl, where you combine lemon peel and sugar, dark rum and cognac, stir well, then take a spoonful of the mixture and light it on fire and return to the punch bowl to set it alight. Dickens would then lift out fiery lemon peels for the guests to admire. Afterwards, the flames are extinguished by a metal tray placed over the punch bowl. Nutmeg was then grated over the punch and ladled out to the guests.

Thursday, December 9, 2021

Traditional Victorian Christmas Dishes by Jenna Jaxon

Another tradition was to serve a rum punch, apparently a favorite Christmastide ritual for Charles Dickens. The making of the punch was quite a production, and Dickens would explain each step to his guests as they watched the punch being concocted. The drink is made in a large fire-proof punch bowl, where you combine lemon peel and sugar, dark rum and cognac, stir well, then take a spoonful of the mixture and light it on fire and return to the punch bowl to set it alight. Dickens would then lift out fiery lemon peels for the guests to admire. Afterwards, the flames are extinguished by a metal tray placed over the punch bowl. Nutmeg was then grated over the punch and ladled out to the guests.

Friday, December 3, 2021

Traditional Regency Christmas

by Donna Hatch

www.donnahatch.com

There's nothing quite like the glimmer of a Christmas tree, brightly wrapped packages, and a yule log burning in the fire to invoke wonder and excitement. But you may be surprised to know that many Christmas traditions are quite new--at least in England. Many English Christmas customs we think are ancient actually sprang up as early as the Victorian Era.

Regency Christmas traditions varied widely from region to region and even

family to family. Generally, the upper classes of Regency England didn't treat

Christmas as a special day beyond a church service and the exchange of small,

mostly hand-made gifts within the family. Ordinary household items such as pen

wipers and fire spills seem to have been common gifts, as well. The middle

classes made a bigger event out of Christmas than their so-called

"betters." Lucky them!

The reason why Christmas became so understated is largely due to Thomas

Cromwell, who served as Chief Minister during the reign of King Henry VIII.

Cromwell and his cronies virtually stamped out Christmas celebrations due to

their origins—pagan licentious superstitions which often resulted in drunken

brawls and even vandalism. Although I seldom approve of the destruction of any

holiday, I can’t really blame him for his disapproval of that sort of

misbehavior.

Fortunately, the Restoration revived Old Christmas into a new, toned-down version of its former bawdy revelry to one of quiet worship and time together with family. During the Regency, more and more celebratory customs cropped up. I suspect many families had practiced some of those customs all along secretly. Yorkshire is an area that seemed to hold on the most tightly to the Old Christmas traditions and enjoyed them openly when it became acceptable.

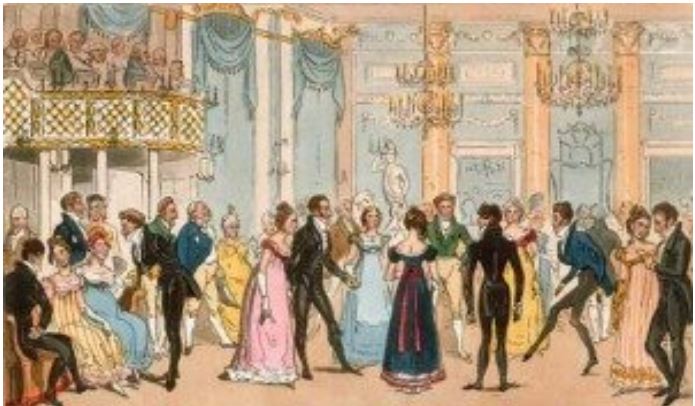

While researching English Christmas customs, I found journal entries and letters describing family events at the Big House, many of which I incorporated into my newest novel, Christmas Secrets. I exercised my creative license to have the local tradition include a ball at the Great House, gathering greenery including a mistletoe "kissing ball," the Yule Log, and singing carols, along with other fun aspects of the season on Christmas Eve.

Largely thanks to Queen Victoria's husband bringing his German traditions

with him to England, which spread to the United States, Victorian Christmas

customs grew into the ‘traditional’ Christmas we all know and love, complete

with carolers, a wider variety of gifts and recipients, Yule logs, Christmas

puddings, cards, Christmas trees, many of the carols we sing today.

Travel in winter in England during the Regency was extremely hazardous,

therefore it was rarely done. By in large, Christmas house parties had to wait

until railroads made winter journeys more feasible, which happened after 1840.

Of course, I and every other author I have read largely ignore this, although

in some of my Christmas stories, I mention people not wishing to travel far due

to the weather.

An odd custom that does date back centuries is telling scary ghost stories. This age-old tradition dates so far back that I couldn’t find its true origin. Aside from the traditional Christmas story, A Christmas Carol, I’m happy that telling ghost stories is no longer part of most family Christmas customs. Can you imagine getting a child to bed who is both excited about Santa’s presents and frightened of ghosts? Now that is scary!

In the mood for a little holiday romance? Check out my Christmas novel, Christmas Secrets,

which features a ghost, and kiss, and a happily-ever-after.

Sweet Regency Christmas

Christmas Secrets

A stolen Christmas kiss leaves them bewildered and breathless.

A charming rogue-turned-vicar, Will wants to prove he left his rakish days

behind him, but an accidental kiss changes all his plans. His secret could

bring him together with the girl of his dreams...or divide them forever.

Holly has two Christmas wishes this year; to finally earn her mother's approval

by gaining the notice of a handsome earl, and to learn the identity of the

stranger who gave her a heart-shattering kiss...even if that stranger is the resident

Christmas ghost.

Wednesday, November 3, 2021

Bound for Eternity: The Custom of Scottish Handfasting by Jenna Jaxon

Friday, October 15, 2021

Early in my writing career, the best piece of writing advice I ever got—right behind “be persistent”—was “write what you love.” So I did. I wrote everything because I loved everything, but eventually settled on historical romance.

I’ve always loved historical fiction. As a child, I devoured Anne of Green Gables, Little Women, the Little House books, The Secret Garden and A Little Princess. Later I discovered Jane Eyre, the Jane Austen novels, and other historical classics. But again, I craved more romance. Fortunately for me, historical fiction was a hot market. The hard part was finding a book clean enough for me because I don’t like to read hot sex scenes. Once I discovered traditional Regency romances, which were generally very clean, sweet romances, I was in heaven. It was not to last, however.

Historical fiction's popularity waned, and for about a decade, sales across the board plummeted. Perhaps readers tired of hot, sexy romance novels referred to as “bodice rippers” and "clean and wholesome" romance novels had not yet become a category. Instead, they were termed Traditional Regencies, which enjoyed success for a while, but they, too, fell out of popularity. The worst blow came when I learned two major traditional Regency romance publishers closed their doors. The news broke my heart, not only because I loved reading them, but because I’d written a sweet, traditional Regency romance novel that I’d been hoping they’d publish. For a long time, people called historical romance—and Regency romance in particular—a “dead” market. Sob!

Good news! Historical Romance novels, specifically Regency Romance novels, have regained popularity. Sales are skyrocketing for all historical romance, both on the hotter side and those sweeter, more traditional romances such as what we expect from Jane Austen era novels or Georgette Heyer. Personally, I love a clean romance, and if it’s a clean historical romance—even better!

As a historical author, I had to wonder; why the return of the historical romance?

I think there are many reasons. One is with all the recent movies based on famous books such as all the Jane Austen's, North and South with the dreamy Richard Armitage, and many other historical novel adaptations, especially Jane Austen adaptations, a whole new generation of fans have been converted to historical stories--historical romances in particular.

Another reason I believe historical romance novels have regained popularity is because most people read either to relax or escape (and escaping is part of relaxing, don’t you think?). We crave a true escape from the modern world with all our troubles that only a journey into new world can provide. Maybe it’s the fantasy element of vicariously living the life of the very rich, wearing beautiful gowns, having handsome heroes vie for our favor or even dueling over our honor.

In Regency England, manners were very formal. There was a protocol to everything from how many sets a lady could dance with a gentleman in one evening (two), to what to wear while walking (a walking gown).

I love the way people in Regency England spoke so eloquently. They also prized wit and they excelled in using the understatement. As a historical author, I try to bring that out in every historical novel I write.

Regency men were civilized and treated women with courtesy. When a lady entered the room, gentlemen stood, doffed their hats, curtailed their language, offered an arm, bowed, and a hundred other little things I wish men still did today. But they were also very athletic; they hunted, raced, fenced, boxed, rode horses. They were manly. Strong. Noble. Resolute. Honorable. And that is why I love them!

I hope that historical romance is a here-to-stay market.

What do you love best about historical novels or historical romance?

Wednesday, September 1, 2021

The Regency Swoon by Jenna Jaxon

Friday, August 13, 2021

Regency Introductions, how to meet new people

by Donna Hatch

In our informal modern society, it’s socially acceptable to introduce ourselves to a stranger without needing a third person to get involved. Meeting someone new might start with a clever (or corny) pick up line or be as simple as saying, “Hi, my name is____.” We can be confident that the other person will tell us his or her name. And thus an acquaintance, or more, begins.

During the Regency, an introduction was much more than just discovering someone’s name. If you’ve seen Austen or other historical adaptations on television or film or read them in books, you’re probably familiar with the concept of an introduction. When a lady catches a gentleman’s eye, he would ask a common acquaintance to introduce him to the heroine. If they were at a ball or a soiree, he would likely ask the hostess for the introduction. He would never simply present himself to her. The same goes for meeting anyone with whom one did not already have an association.

In a formal social setting such as a ball, the introductions would be performed by a hostess, a patroness at Almack’s, or the Master of Ceremonies at an assembly room.

If one allowed someone to present another person to him or her, one was accepting the relationship because an introduction was a sort of recommendation. If a hostess presented a gentleman to a lady, the hostess was, in essence, recommending him to the lady based on his character, rank, status, etc. Only after the introduction had been made could the relationship begin.

Basic Rules for Introductions in the Regency:

- A gentleman is introduced to a lady, regardless of rank

- A younger person is introduced to an older person, regardless of rank

- If they are of the same gender and similar age, the lower-ranking person is introduced to the higher-ranking person

- Everyone is introduced to royalty

- One never introduces oneself to another person--one must be introduced by a mutual acquaintance

The lady or the higher-ranked person may decline the introduction. So, at a ball, a lady--or her chaperon--could refuse an introduction to someone whose acquaintance was considered undesirable. In all honesty, I have yet to encounter a written instance when someone rejects a request for a presentation, but it does leave a great deal for the imagination, doesn’t it? It could be so deliciously awkward! But keep in mind, such an act would probably snub the third party who asked to make to introduction.

Though this is later in the century, Routledge’s Manual of Etiquette 1899 has great insight on this concept:

To introduce persons who are mutually unknown is to undertake a serious responsibility, and to certify to each the respectability of the other. Never undertake this responsibility without in the first place asking yourself whether the persons are likely to be agreeable to each other; nor, in the second place, without ascertaining whether it will be acceptable to both parties to become acquainted.

So, the third person should have given some thought as to whether this would be a mutually beneficial introduction. By accepting an introduction, the lady welcomes the relationship.

However, balls are a different animal. This same guide makes this statement:

At a ball, or evening party where there is dancing, the mistress of the house may introduce any gentleman to any lady without first asking the lady’s permission.

This is probably because it is assumed that the hostess gave serious thought to her guest list, so she can safely assume if she accepts them all, they all ought to accept each other.

Also, an introduction at a ball or assembly was not considered an introduction anywhere else but that particular event. If, however, the lady or the higher-ranking person first acknowledges the other in a different setting the next time they meet, then the first introduction can carry over as a non-event-specific introduction. I know, it seems odd and overly stuffy to us in these days, but the Regency era was a very different time.

Once the introduction is made, the lady would be expected to make herself available to dance with the gentleman--unless she was not dancing at all or already promised the dance to another.

When two gentlemen are being introduced, the person of the higher also has the option of accepting or rejecting. If he accepts, he’s basically accepting the other man’s association into his social circle.

How it Wasn’t Done

Presenting oneself to another is a major social faux pas, as we see from Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice (1813). When Mr. Collins proposed to introduce himself to Mr. Darcy, his superior in rank, Elizabeth is appropriately shocked, as evidence by her reaction:

“You are not going to introduce yourself to Mr Darcy!”

“Indeed I am. I shall entreat his pardon for not having done it earlier. I believe him to be Lady Catherine’s nephew. It will be in my power to assure him that her ladyship was quite well yesterday se’nnight.”

Elizabeth tried hard to dissuade him from such a scheme, assuring him that Mr Darcy would consider his addressing him without introduction as an impertinent freedom, rather than a compliment to his aunt; that it was not in the least necessary there should be any notice on either side; and that if it were, it must belong to Mr Darcy, the superior in consequence, to begin the acquaintance.

Mr. Collins, of course, dismisses her advice. His presumption in addressing the lofty Mr. Darcy received an appropriate response:

Mr Darcy was eyeing him with unrestrained wonder, and when at last Mr Collins allowed him time to speak, replied with an air of distant civility. Mr Collins, however, was not discouraged from speaking again, and Mr Darcy’s contempt seemed abundantly increasing with the length of his second speech, and at the end of it he only made him a slight bow, and moved another way.

This ill-mannered ruffian who was related to the Bennets no doubt added further proof that Elizabeth’s family was uncultured, contemptible, and therefore unworthy of Mr. Darcy’s notice.

According to The Social Historian, Victorian Etiquette,

No gentleman should ask a lady to dance unless he has previously met her acquaintance. An introduction can be arranged through the Master of Ceremonies or through the lady of the house or a member of her family. Should a lady be approached by a man to whom she has not been introduced, she should reply that she would accept his invitation with pleasure if he would first procure an introduction.

How to Perform an Introduction

Manners and Rules of Good Society (1888) states:

The correct formula in use when making introductions would be to say, ‘Mrs X – Lady Z,’ thus mentioning the name of the lady of lowest rank first, as she is the person introduced to the lady of highest rank. It would be unnecessary and vulgar to repeat the names of the two ladies in a reversed manner – thus, ‘Mrs X – Lady Z. Lady Z – Mrs X.’

This makes sense because if a gentleman asked to be introduced to a young lady, it stands to reason that he’d already have gone to the trouble to inquire as to her name, and possibly has asked enough about her to decide if he desires to make her acquaintance.

That being said, it is possible to introduce two people. Northanger Abbey (1817), gives an example of a two-way introduction:

The young ladies were introduced to each other, Miss Tilney expressing a proper sense of such goodness, Miss Morland with the real delicacy of a generous mind making light of the obligation.

Perhaps, then, it depends on the situation. If adults are introducing their children to each other in the hopes that a friendship, or more, might result, there would be a two-way introduction such as “Oliva, dear, please meet Miss Rose Jones, the youngest daughter of our newest neighbor, Mr. Jones. Miss Jones, this is my eldest daughter, Olivia.”

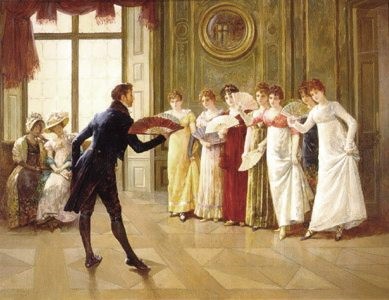

Imagine a handsome lord sees a lovely lady across a crowded ballroom. Intrigued, he asks his hostess who she is. Upon learning a little about her, and more determined than ever to make her acquaintance, he begs to be introduced to this vision who has piqued his interest.

The introduction would be something like, “Miss Palmer, I'm pleased to introduce Lord Amesbury.”

One look into her eyes changes him forever.

And their story begins…

References:

The Pocket Book of Etiquette by Arthur Freeling

The Social Historian, Victorian Etiquette

Regency introductions - a Regency History guide by Rachel Knowles

Wednesday, July 7, 2021

Regency Parlor Games: Charades by Jenna Jaxon

Charades was invented in 16th century France and became very popular in Britain by the time of the Regency. Unlike our contemporary version, during the Regency the game wasn’t carried out in silence with contestants acting out the words of the answer. Instead, a riddle was spoken that gave clues to the syllables of a word then a description of the whole. And the whole thing had to rhyme.

The first one to guess the charade won.

Charades was a popular game with Jane Austen, both to play with her family and guests and as an entertainment for her characters in several of her novels.

Some people created their own charades, but many were published in books and magazines so people could use them ready-made. Sometimes they were printed on ladies' fans, with the answer on the reverse side. Usually the charades are in three parts, the first denotes the first syllable, the second, the second syllable, and the third describes the whole word.

Below are a couple of charades printed in the book Riddles, Charades, and Conundrums, complied by John Winter Jones in 1822.

(1)

My first, whatever be its hue,

Will please, if full of spirit;

My second critics love to do,

And stupid authors merit.

(2)

My first a blessing sent to earth,

Of plants and flowers to aid the birth;

My second surely was design’d

To hurl destruction on mankind:

My whole a pledge from pardoning heaven,

Of wrath appeas’d and crimes forgiven.

In the Victorian period the game changed to include acting out the words without words (in Jane Eyre the company plays charades and acts out the word Bridewell in silence). And has continued on that way to the present day.

Solutions:

(1) Eye-lash

(2) Rainbow

Wednesday, June 2, 2021

The Erotic Art of Thomas Rowlandson by Jenna Jaxon

Wednesday, May 5, 2021

The Dress Act of 1746 by Jenna Jaxon

Wednesday, April 7, 2021

Unmentionables: A Brief History of Underwear by Jenna Jaxon

Wednesday, March 3, 2021

18th Century Medicine: Trepanation

Friday, February 12, 2021

As a romance author and hopeless romantic, I cannot possibly ignore Valentine’s Day. I admit, until I started researching the topic, I really didn't know the real history behind Valentine’s day except it was to honor a Christian named Valentine who was martyred for marrying people in secret. Which really didn't make sense to me. Was he martyred because he was Christian? Or because he was marrying people? To my surprise, I found the answer to be a bit of both. Maybe. Although no one really sure who, exactly the famous Valentine actually was. He may have actually been more than one person. Much is couched in myth and speculation. However, here's some fun history, sprinkled liberally with legend.

This much appears to be factual: In Rome 270 C.E. Emperor Claudius II put out an edict saying no man could marry. Ever.

??????

Talk about a stupid law! No marriage? At all? And sex outside of marriage was considered to "prostitution" which was also illegal. Talk about a bunch of lonely, unhappy people. And how were children to be brought into the world? Did he think it was okay for his entire country to become extinct in a single generation? Clearly, this brainless emperor didn’t think that one through.

He apparently did have a reason for it, however short-sighted. He felt that marriage made men "soft" and therefore unreliable soldiers. Men wouldn’t want to leave his wife and child AND die for his country, and because Emperor Claudius needed a massive army to maintain his vast empire. So, he outlawed marriage. Clearly, he wasn't worried about becoming unpopular with his crazy law nor having a country peopled with soldiers for his posterity.

Into this confusing chaos steps Valentine, the Bishop of Interamna, who invited all young lovers to come secretly marry and, in turn, converted quite a few people to Christianity. This man was intelligent – much smarter than the Emperor because while getting his way of converting people to Christianity, he also saw to the needs of disgruntled lovers. Aw, isn’t that sweet?

Into this confusing chaos steps Valentine, the Bishop of Interamna, who invited all young lovers to come secretly marry and, in turn, converted quite a few people to Christianity. This man was intelligent – much smarter than the Emperor because while getting his way of converting people to Christianity, he also saw to the needs of disgruntled lovers. Aw, isn’t that sweet?

Or it might have been a ploy to convert heathens. Either way, the Emperor inevitably found out and had Valentine arrested.

The odd thing is, Valentine may not have been condemned for going against the Emperor's edict. Some accounts suggest it was because he refused to renounce Christianity and convert to Roman ways AND even attempted to convert the Emperor to Christianity. Talk about pluck! According to legend, while Valentine was awaiting execution, he befriended a girl who was the blind daughter of the jailer. While in jail, Valentine restored her eyesight through his faith. Some people believe he fell in love with her. Then he supposedly wrote her a farewell letter on the day that he was stoned (or beaten, according to some sources) and then beheaded. Another account reports he simply died in prison, probably of typhus, or gaol (jail) fever. At any rate, Valentine reportedly signed his love letter, "FROM YOUR VALENTINE."

We have been using his name, and even that phrase, ever since.

Also, there appears to have been anywhere from three to seven men who bore that name and were martyred, or died while in service to the church. Apparently one helped a number of Christians escape prison where they were being beaten and tortured. This Valentine was caught and executed. Another Valentine was a missionary in Africa, but little is known about him. Or, it’s possible, they were all the same men, but accounts of his death have been muddied. However, we do know that Valentinus, or Valentine, was a very common Roman name.

Though the marrying Valentine was executed on February 24, (according to some sources, anyway) 270, the Christian church chose to honor him and all the Valentines – who all supposedly died on or near February 14 – on February 14th because they wanted to replace a Roman rite of passage to the God of Lupercus. Part of the festival included men running around and slapping young women with a strap dipped in blood with the idea it was supposed to make them fertile. Another practice in that festival involved putting the names of virgins in a box (I wonder if they were willing or unwilling?) and drawn by not so virginal men (ARE there any virginal men?) in a lottery. Whichever girl was drawn was then assigned to "pleasure" the lucky man until the next lottery, which was a year later. (poor girl!!!) Sounds like a premise for a book, doesn’t it?

Anyway, the church was appalled by this pagan holiday (I don't blame them) so they chose to substitute it with a close second. Well, okay, maybe by the men’s standards it wasn’t such a close substitute. But Valentine’s Day appealed to the love aspect of the ritual instead of sex. I’m sorta surprised the men went for it, men being what they are. But I guess pleasing his wife, or the girl whom he hopes will be his wife someday, in the hopes he’ll get lucky (ahem) was the best substitute a good Christian man could hope for.

So, happy Valentine's day! And be grateful we aren't Roman!!!