by Donna Hatch

Next to Robin Hood’s Merry Men, few other groups inspire images of mystery and intrigue quite as well as Bow Street Runners. They were a unique and unprecedented fighting force that paved the way for London’s modern police, Scotland Yard. They are also no longer in existence, and very little is actually known about them. Hence the mystery. And the tragedy.

Next to Robin Hood’s Merry Men, few other groups inspire images of mystery and intrigue quite as well as Bow Street Runners. They were a unique and unprecedented fighting force that paved the way for London’s modern police, Scotland Yard. They are also no longer in existence, and very little is actually known about them. Hence the mystery. And the tragedy.Before the Magistrate of Bow Street formed the famous Runners, there was no real organized police force and no true police procedures. Constables in London were virtually untrained and failed to do much to protect the innocent or bring justice to the guilty. A Night Watch made up on a rotating basis by the men in a particular district. However, most working-class men wouldn’t or couldn’t be up all night keeping watch. Besides, it was dangerous--ruffians and thugs they tried to arrest usually fought back. Some of these members of the Nigh Watch hired out others to take their turn. Often elderly men who needed the money because they could no longer work filled these roles. These night watchmen typically huddled in groups around the nearest light and hoped no one would harass them. Needless to say, they were an ineffective deterrence to most thieves.

Therefore, the average citizen performed most arrests. The citizen who’d been wronged had to gather all his own evidence, perform the arrest, drag the person before the magistrate (judge) and convince the magistrate this was their man. This citizen served as investigator, policeman, and lawyer all in one--a daunting task, to be sure. Although since the accused were considered guilty unless proven innocent, receiving a guilty verdict was usually a no-brainer. I'm sure some took advantage of this system to seek revenge for wrongs that had little to do with the law.

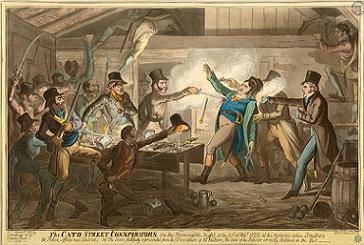

Into this ineffective chaos stepped the Fielding brothers. Henry Fielding was a magistrate who operated his office on Bow Street. In 1750, he organized an elite fighting force of highly trained and disciplined young men known as the Bow Street Runner. also nicknamed the “Robins Redbreasts” for their distinctive red waistcoats (sometimes spelled weskits because that's how it's pronounced). Bow Street Runners, who, according to research, preferred the term constables, were trained to conduct investigations including rudimentary forensics, and how to question witnesses and victims. They even carried handcuffs. How early they began carrying these restraints and wearing the red waistcoats is anyone’s guess, but in St. Ives by Robert Lewis Stevenson, written in 1897, described Bow Street Constables with handcuffs and red waistcoats.

In the early years, there were only six Bow Street constables in London. For some reason, that number was kept constant at first. But later, those figures grew and there was even a mounted patrol who protected the highways leading outside of London from the dreaded and dangerous highwaymen. This mounted patrol changed safety, and therefore nature, of travel.

While the office of a magistrate belonged exclusively to gentlemen of the nobility or landed gentry, the Bow Street constables were working-class men. They were smart, skilled, well-trained, and cunning. The Fielding brothers hand-picked them for the position. Though the constables of Bow Street typically remained in the London area, there are accounts of them tracking fugitives as far as the Scottish border. They drew a modest salary from Bow Street, so most of their pay came in the form of a bounty or reward, usually paid by the victim or a group who had a vested interest in solving a crime. Runners were also hired out to conduct special investigations, and to act as bodyguards. I have found no evidence of foul play or bribes taken, suggesting that they were men of honor and that they had strong loyalty to their magistrate who was always a man of integrity.

While the office of a magistrate belonged exclusively to gentlemen of the nobility or landed gentry, the Bow Street constables were working-class men. They were smart, skilled, well-trained, and cunning. The Fielding brothers hand-picked them for the position. Though the constables of Bow Street typically remained in the London area, there are accounts of them tracking fugitives as far as the Scottish border. They drew a modest salary from Bow Street, so most of their pay came in the form of a bounty or reward, usually paid by the victim or a group who had a vested interest in solving a crime. Runners were also hired out to conduct special investigations, and to act as bodyguards. I have found no evidence of foul play or bribes taken, suggesting that they were men of honor and that they had strong loyalty to their magistrate who was always a man of integrity.Magistrates in other districts of London followed the Fielding’s example by having a specific group of effective investigators--for example, the Thames River Police--but none achieved the lasting acclaim that the Bow Street constables did.

In 1830, when Scotland Yard was organized, the Bow Street constables became obsolete. Much of Scotland Yard’s procedures evolved from those created by Bow Street, and I can only assume that many constables became investigators for Scotland Yard. Progress is usually a good thing, but I feel a sense of loss whenever something unique is swept away to make room for something "better."

In my newest book, Not a Fine Gentleman, the hero is a Bow Street Constable hired to hunt down a murder suspect and bring her to justice. But this assignment is different, and not just because sparks fly between him and the lady accused of murdering her husband. This romantic story of loss and betrayal, forgiveness and redemption, will leave you laughing, crying, and swooning. Sprinkled liberally with suspense, mystery, and heart-melting kisses, this is not your ordinary historical romantic suspense. Fans of Victorian and Regency Eras, and those seeking clean and wholesome romance with plenty of chemistry, will love this story!

Here is the link to buy your own copy of NOT A FINE GENTLEMAN. It’s free on Kindle Unlimited and also available in print.

Lady Margaret secretly yearns for love, but fate has exchanged wedded bliss for a lie. When she is caught hovering over her cheating husband's dead body, she is instantly doomed to hang for his murder. Without hope for justice, unless she takes matters into her own hands, Margaret flees into the night alone.

A cynical Bow Street Constable, Connor Jackson, vows to bring the fugitive Lady Margaret to face the law—but, he doesn’t expect sparks to fly between them. Could the strong yet tender lady truly be a killer?

As more suspects—and even more condemning evidence—surface, the less certain Connor is of his duty. He must choose between his growing feelings for Lady Margaret and the demands of justice. Will the truth tear them apart or set them free to find love?

NOT A FINE GENTLEMAN is free on Kindle Unlimited and also available in print.