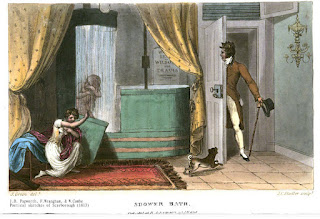

Last month I took a look at bathing and bathtubs in the Regency period. This month I’m going backward in time to examine bathing during the Middle Ages.

The first thing to affirm is that yes, people did bathe

during the Medieval period, using several different methods.

A lot depended on your status in life as to how often you took a bath. The lowest classes who did manual labor likely bathed the least. They would probably not have had the means or money to fetch buckets of water, heat the water, and purchase a tub and then bathe in it. Such laborers and the poorer people would have availed themselves of a dip in a pond, lake, or stream during the warmer months. Otherwise, they may have taken wash pan baths, washing as best they could during the colder months.

Middle class people may have had enough money to own a

tub and employ a servant to fetch and heat the water. They might also have had

the fees to go to public bath houses (a holdover from Roman times). These

houses were very popular but had a reputation for lewdness. The sexes weren’t

always separated, and prostitutes were known to frequent them.

The nobility would have had a tub for the household to use (perhaps more than one, depending on the

size of the family). Tubs were a status symbol for the wealthy. They would be lined with linen fabric to protect tender skin from splinters if the tub was wooden, or to protect it from seams if the tub was made of metal.

Royal households would certainly have availed

themselves of the bath. Documents show that Charlemagne loved taking baths and

not just alone. He’d invite relatives, guests, and sometimes servants and

attendants to bathe with him. King John of England took a bathtub with him when

he traveled.

One additional note of interest: men usually bathed naked while women wore a shift or chemise, whether for warmth or modesty is difficult to tell.

So bathing, in all its various forms, was definitely a

large part of life during the Middle Ages.

Resources:

Chase, Loretta. “Queen Caroline Takes a Bath.” Two

Nerdy History Girls, July 11, 2011.

“Did People in the Middle Ages Take Baths?”

Medievalists.net, April 2013.

Peardon, Keri. “Bathing in the Middle Ages.” Vampires,

Ladies, and Potpourri, June 14, 2012.